- Home

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

To Mary and David—

“Happily, happily foreverafterwards —the best we could.”

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Illustrations in Text

Zelda Sayre, 1918. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Lt. F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1918. Courtesy of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated

Facsimile of Scott’s August 1918 letter to Zelda. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Auburn football star Francis Stubbs, from Zelda’s scrapbook. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Facsimile of Scott’s March 24, 1919, note to Zelda. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Facsimile of last page of Zelda’s March 1919 letter to Scott, with drawing of a kiss. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Zelda in Follies costume, 1919. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Scott and Zelda in Montgomery, March 1921. Copyright Bettmann/Corbis

Scott and Zelda, embarking on “The Cruise of the Rolling Junk.” Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Frances Scott Fitzgerald. Courtesy of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated

Zelda and Scottie, 1922. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

The Fitzgeralds, Christmas 1925, Paris. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Scott, Zelda, and Scottie in Annecy, July 1931. From The Romantic Egoists, edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli, Scottie Fitzgerald Smith, and Joan P. Kerr

Les Rives de Prangins. Courtesy of Matthew J. and Arlyn Bruccoli Collection of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina

Zelda’s room at Prangins. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Scott and Scottie skiing at Gstaad, December 1930. Courtesy of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated

Facsimile of Zelda’s closing to August 1931 letter to Scott. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Facsimile of Zelda’s March 1932 letter to Scott with Scott’s notations. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Dust jacket photograph of Zelda for Save Me the Waltz. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Scott and Zelda attending a theater performance of Dinner at Eight, Baltimore 1932. Courtesy of Arthur Mizener’s Estate

Newspaper picture of the Fitzgeralds on their lawn after the fire at La Paix in June 1933. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Scott and Scottie in Baltimore, while Scottie was a student at the Bryn Mawr School. Courtesy of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated

Facsimile of Zelda’s May 1934 letter to Scott. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

The fourth page of Zelda’s October 1934 letter, with her sketch of Scott, “Do-Do in Guatemala.” Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Scott in North Carolina, 1936. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Zelda in North Carolina, 1936. Courtesy of Matthew J. and Arlyn Bruccoli Collection of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina

Facsimile of pages outlining Zelda’s expenditures, March/April 1938. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

Scottie at her high school graduation, June 1938. Courtesy of Matthew J. and Arlyn Bruccoli Collection of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina

Self-portrait of Zelda, 1940. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

PREFACE

The most important relationship that either F. Scott or Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald had was that with each other; it was the catalyst for and foremost theme of much of their fiction. The letters they exchanged tell the story of this central relationship in their own words; those that have been previously published in editions of Scott’s correspondence and in Zelda’s Collected Writings have never before appeared together in one volume. In addition, there are many unpublished letters in the Princeton University library, and these deserve to be part of the record, as well. The Fitzgeralds’ courtship and marriage has become a compelling and enduring part of our literary history. The new letters, placed chronologically with those collected previously, allow us to view their relationship in a more evenhanded manner than heretofore has been possible.

The most detailed and accurate account of the Fitzgeralds’ relationship is still Nancy Milford’s best-selling Zelda: A Biography (1970). Milford was the first not only to explore the many letters Zelda wrote to Scott but also to attempt putting them in some kind of order. In the prologue to Zelda, Milford recalls how she and her husband read the letters aloud to each other “as if they had just arrived, not knowing from what terrain of their lives they had been written or what the next one would say. They were hopelessly mixed up and undated, without, in most cases, envelopes to give them dates. . . . I had somewhat innocently . . . entered into something I neither could nor would put down for six years . . .” (xiii). Much of Milford’s account is based on these letters, from which she quotes extensively; yet only a sampling of them could appear in her biography, and even then only in a highly truncated form. Now, for the first time, we can read those intriguing letters from Zelda to Scott for ourselves.

Over thirty years have passed since the Milford biography, and, as a society, we have learned much (though still not enough) about the nature of mental illness (from which Zelda suffered) and alcoholism (from which Scott suffered). Yet this knowledge has not been reflected in what has been written about the Fitzgeralds. The tendency has been to sensationalize their lives and illnesses.

Scott and Zelda’s lives were indisputably dramatic and tragic, and therefore all too easy to distort. Perhaps the most sensational myth of all is the persistent claim that Scott, jealous of his wife’s creativity, suppressed her talents and drove her mad. Koula Svokos Hartnett’s view of the Fitzgeralds’ marriage, in Zelda Fitzgerald and the Failure of the American Dream for Women (1991), regrettably is all too representative: “As his appendage, [Zelda] was to become the victim of [Scott’s] self-destructive urge. In denying her the right to be her own person . . . , by refusing to permit her the use of her own material . . . , by rebuking her for attempting to create a life of her own—he gradually causes her to emotionally wither and die” (187). Such an assertion defies common sense as well as even the most fundamental understanding of mental illness; yet it has gained some general acceptance. For further evidence that this view persists, one has only to look at the most recent biography of the Fitzgeralds, published in 2001 and claiming to be definitive, in which Kendall Taylor asserts:

She [Zelda] had used up her life providing material for a writer who to this day is considered one of America’s greatest, yet as a man and husband was cunningly controlling. When she finally tried to make a life for herself, apart from the marriage, it was too late. She had scant resources left. The only way out was through the insanity to which her family was prone. In writing the epigram “sometimes madness is wisdom”1 she was revealing the paradigm of her life. (Sometimes Madness Is Wisdom 372–373)

The suggestion of mental illness as an escape (“[t]he only way out”) echoes this passage from Zelda in which Milford makes the same suggestion when discussing Zelda’s first breakdown in 1930:

Ahead of them [Scott and Zelda] would be the slow agony of putt

ing the pieces of their lives together again. . . . She was diagnosed . . . as a schizophrenic, and not simply as a neurotic or hysterical woman. It was as if once Zelda had collapsed there was no escape other than her spiraling descent into madness. . . . To record her breakdown is to give witness to her helplessness and terror, as well as to explore again the bonds that inextricably linked the Fitzgeralds. (161)

Despite this somewhat vague insinuation, Milford’s biography remains well researched and the most trustworthy exploration of Zelda’s side of the Fitzgeralds’ relationship to date, far more careful and accurate than Taylor’s, which contains factual errors as well as insupportable assertions.

The new Taylor biography probably is not all that important in itself, but it does represent for the first time a full-length study guided by a viewpoint that has ridden the wave of contemporary criticism for the past thirty years. The Fitzgeralds’ marriage was a chaotic one, but it is no more reasonable to say that Scott drove his wife mad than it is to say that Zelda drove her husband to drink. Although Zelda and Scott married young, their inherited predispositions to mental illness and alcoholism, respectively, were already present. These traits were apparent in the impulsive behavior that characterized their courtship and actually fed their attraction for each other from the beginning. Although stories of the descent into madness and alcoholic binges may create exciting reading, they do little to further our understanding and appreciation of these two gifted and troubled human beings who have captured and held our attention as readers all these years.

Even more disturbing is Taylor’s statement that her argument is substantiated by Zelda’s letters, indicating that her biography presents Zelda’s point of view regarding the marriage:

Nowhere is the reality of the Fitzgeralds’ marital situation more evident than in Zelda’s superbly crafted letters to Scott. These number in the thousands, and Fitzgerald saved all of them. Much of my book has been drawn from them, because they provide the greatest understanding of Zelda’s character. (xiv)

This assertion is disturbing because it is inaccurate. The total number of Zelda’s letters to Scott that survive at Princeton is closer to five hundred than to thousands; and although we agree that the letters are superb, they are not “crafted”: Zelda wrote spontaneously, impressionistically, and quickly. Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda, which features virtually all of Zelda’s previously published letters, along with a substantial selection of those previously unpublished, allows readers to see for themselves just how Zelda viewed her marriage to Scott at each stage of the relationship.

At times, the Fitzgeralds did blame each other for the things that went wrong in their lives, including problems in their marriage. During the years 1932 through 1934, they often had bitter arguments over who had the right to fictionalize material based on their lives. Their letters certainly represent these periods of anger, but the greater portion express concern over the hardships endured by the other and an appreciation of each other’s accomplishments despite formidable obstacles. Although conflict is an important aspect of their relationship, and not to be minimized, when we look at the entire relationship, we can see that it is not competition that emerges as the defining characteristic of their marriage, but love and mutual support, hampered as that support might have been by the serious illnesses the Fitzgeralds struggled with, which, unfortunately, did dominate their lives.

Although Zelda’s painful struggle with mental illness has been viewed sympathetically, such has not been the case with Fitzgerald’s alcoholism (and the deterioration of his physical health it caused), which has often been viewed as disgraceful behavior on his part, not as the devastating disease we understand it to be today. Scott himself, of course, did not understand the disease, either, only the humiliation it caused. In addition to being insensitive to Scott’s alcoholism, the view that he cruelly stifled Zelda’s creativity neglects the dire position he was in, struggling to pay bills (including those for Zelda’s doctors and hospitalizations) by practicing the only profession he knew—writing. Despite the decline of his reputation and health, he somehow continued to write, just as Zelda, despite the crippling disintegration of her personality, continued to write and paint, and to dream of getting a job and being able to support herself. Ironically, the central value this sensationalized couple held in common was the work ethic; as their letters attest, it was the guiding principle they ultimately valued above all others. Perhaps the most enduring impression of the Fitzgeralds that emerges from their letters is the courage, beauty, and insight born of their deep but tormented love.

EDITORS’ NOTE

In an effort to retain the distinctive flavor of Scott’s and Zelda’s epistolary styles, we have attempted to transcribe their letters as literally as possible, consistent with a reader’s ability to understand them. Thus, we have not corrected spelling errors—of which they both made many—and have inserted corrected spelling (of full words or of letters within words) in brackets only in cases where we felt it necessary to make meaning clear. Similarly, their punctuation is frequently erratic and inconsistent; we have inserted bracketed punctuation only to clarify meaning. All ellipses in the texts of letters are in the originals, unless otherwise indicated. Zelda also used dashes of varying lengths throughout her letters; her use of them is more pervasive in her early correspondence, however, then diminishes in the letters she wrote during the 1930s. Our practice has been to retain many of these (standardized to a one-em dash in length) but to convert some to periods when they occur at the ends of sentences.

Conjectural readings and omitted, obliterated, or illegible words are also indicated in brackets in the text. All words underlined by the Fitzgeralds, either with one line or several, are rendered in italics. In the headings for each letter, we have indicated the date and return address; these are almost always indicated in brackets and are based on internal evidence, because most often such information was not supplied in the original. The following abbreviations have been used in the headings to denote the true form of any given letter: AL—autograph letter unsigned; AL (draft)—unsigned autograph letter found only in draft form; AL (fragment)—autograph letter found only in a fragment; ALS—autograph letter signed; AN— autograph note unsigned; TL—typewritten letter unsigned; TL (CC)—typewritten letter found only in a carbon copy; TLS—typed letter signed; and Wire—telegram. The number of pages cited at the head of each letter refers to the number of sides of paper on which the letter was written. The original copies of all but a very few items of the correspondence in this edition are in the Princeton University library, either in the F. Scott or Zelda Fitzgerald Papers; items found in the Fitzgeralds’ scrapbooks, which are also at Princeton, are so indicated. The location of the very few original items not at Princeton is footnoted.

In providing footnotes, we have attempted to strike a balance between giving needed information and overburdening the reader with excessive scholarly apparatus. We have not identified persons we deemed familiar to most readers; nor have we attempted to do so when a general identification is obvious from context—for example, the many Montgomery friends Zelda mentions in her early letters. Generally, those persons, places, and events we have footnoted are identified only once; if persons, places, and events have been identified in our introductions and narrative passages, we do not reidentify them in footnotes. Nationalities of persons footnoted are given only when such persons are not American.

In order to make our narratives more concise, sources for quoted material are indicated in parentheses in abbreviated form. The full references (and the abbreviation) for such citations are as follows:

Bruccoli, Matthew J. Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981: Some Sort of Epic Grandeur.

———, ed. F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters. New York: Scribners, 1994: Life in Letters.

———, ed., with the assistance of Jennifer McCabe Atkinson. As Ever, Scott Fitz—: Letters Between F. Scott Fitzgerald and Hi

s Literary Agent Harold Ober 1919–1940. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1972: As Ever, Scott Fitz—.

———, and Margaret M. Duggan, eds., with the assistance of Susan Walker. Correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Random House, 1980: Correspondence.

———, Scottie Fitzgerald Smith, and Joan P. Kerr, eds. The Romantic Egoists: A Pictorial Autobiography from the Scrapbooks and Albums of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. New York: Scribners, 1974: Romantic Egoists.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. Afternoon of an Author: A Selection of Uncollected Stories and Essays. New York: Scribners, 1958: Afternoon of an Author.

———. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Ledger: A Facsimile. Washington, DC: NCR/Microcard, 1973: Ledger.

———. The Great Gatsby. New York: Scribners, 1995; originally published in 1925.

———. The Notebooks of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich/Bruccoli Clark, 1978: Notebooks.

———. The Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Scribners, 1951: Stories.

Fitzgerald, Zelda. The Collected Writings. Edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli. New York: Scribners, 1991: Collected Writings.

Hartnett, Koula Svokos. Zelda Fitzgerald and the Failure of the American Dream for Women. New York: Peter Lang, 1991.

Hemingway, Ernest. A Moveable Feast. New York: Scribners, 1964.

Kuehl, John, and Jackson R. Bryer, eds. Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence. New York: Scribners, 1971: Dear Scott/Dear Max.

Lanahan, Eleanor. Zelda: An Illustrated Life. New York: Abrams, 1996.

Milford, Nancy. Zelda: A Biography. New York: Harper & Row, 1970: Zelda.

Mizener, Arthur. The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Revised ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

Taylor, Kendall. Sometimes Madness Is Wisdom—Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald: A Marriage. New York: Ballantine, 2001.

This Side of Paradise

This Side of Paradise The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby Tender Is the Night

Tender Is the Night Tales of the Jazz Age (Classic Reprint)

Tales of the Jazz Age (Classic Reprint) The Beautiful and Damned

The Beautiful and Damned The Pat Hobby Stories

The Pat Hobby Stories The Love of the Last Tycoon

The Love of the Last Tycoon The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Six Other Stories

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Six Other Stories O Grande Gatsby (Penguin)

O Grande Gatsby (Penguin) Babylon Revisited and Other Stories

Babylon Revisited and Other Stories The Crack-Up

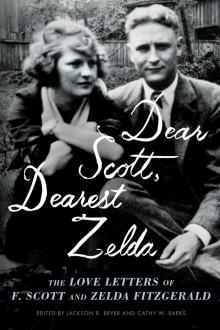

The Crack-Up Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda The Fantasy and Mystery Stories of F Scott Fitzgerald

The Fantasy and Mystery Stories of F Scott Fitzgerald Flappers and Philosophers

Flappers and Philosophers The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories (Penguin Classics)

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories (Penguin Classics) I'd Die For You

I'd Die For You All the Sad Young Men

All the Sad Young Men The Last Tycoon

The Last Tycoon The Best Early Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Best Early Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald This Side of Paradise (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

This Side of Paradise (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) A Life in Letters

A Life in Letters Beautiful and Damned (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Beautiful and Damned (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories Tales of the Jazz Age

Tales of the Jazz Age Babylon Revisited

Babylon Revisited Complete Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald UK (Illustrated)

Complete Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald UK (Illustrated)