- Home

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda Page 8

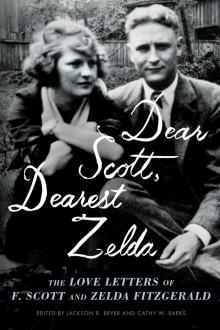

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda Read online

Page 8

Frustrated by this inability to survive financially in expensive Great Neck, Scott and Zelda decided in April 1924 to go to Europe and live on the Riviera, where the exchange rate was nineteen francs to the dollar. “We were going to the Old World to find a new rhythm for our lives,” Scott wrote in an essay he wrote not long after their arrival, “How to Live on Practically Nothing a Year,” “with a true conviction that we had left our old selves behind forever . . .” (Afternoon of an Author 102). Scott had saved seven thousand dollars of his pay from his short stories, and his plan was to work only on his novel until he finished it, which he was able to do. While he was deeply immersed in his writing, Zelda became romantically involved with a handsome young French aviator, Edouard Jozan, in July 1924. Though both Fitzgeralds were later to use this event in their fiction—Zelda in her novel, Save Me the Waltz (1932), and Scott in numerous short stories and his novels The Great Gatsby (1925) and Tender Is the Night (1934)— and while Scott was undeniably devastated by it (he wrote in his Notebook, “I knew something had happened that could never be repaired” [Notebooks 113]), the actual extent of the relationship will probably never be known (Jozan described it as no more than a flirtation).

Whatever the facts, the Jozan-Zelda romance surely contributed to the plot and ambience of the novel Scott completed in late October 1924, his small masterpiece, The Great Gatsby. As he described the book to his friend Ludlow Fowler in August 1924, “the whole burden” of it was “the loss of those illusions that give such color to the world so that you don’t care whether things are true or false as long as they partake of the magical glory” (Life in Letters 78).

It was also on the Riviera during the summer of 1924 that the Fitzgeralds became close friends with wealthy American socialites Gerald and Sara Murphy, whom they had met in Paris in May 1924. The Murphys, in turn, introduced them to their circle of writers, composers, and artists, which included Pablo Picasso, Cole Porter, Archibald MacLeish, Fernand Léger, Philip Barry, Rudolph Valentino, Dorothy Parker, and Robert Benchley. As their motto, the Murphys had adopted an old Spanish proverb: “Living well is the best revenge.” It was during this period as well that Scott first encountered the work of Ernest Hemingway, reading the latter’s short story collection in our time, which had recently been published in Paris, and recommending the young author to his own editor at Scribners, Maxwell Perkins.

Because even the favorable exchange rate in France was proving beyond Scott and Zelda’s means, they decided, after Scott sent Gatsby to Scribners in late October, to spend the winter in Rome and Capri (the exchange rate in Italy was lower than in France). Despite Scott’s dislike of the Italians, Zelda’s bout with colitis, and what Scott described in a letter to John Peale Bishop as “terrible four day rows” between them “that always start with a drinking party,” he was able to make major revisions in the galleys of Gatsby, changes that substantially transformed the novel. And despite the tensions in his marriage, he reassured Bishop in the same letter in which he described the “four day rows” that he and Zelda were “still enormously in love and about the only truly happily married people I know” (Life in Letters 104). By April 10, 1925, the date on which Gatsby was published, the Fitzgeralds were back in Paris. While the reviews were the most positive he received for any of his books, sales were extremely disappointing (a first printing of twenty thousand sold out in a few months, but copies of a second printing of three thousand were still in a Scribners warehouse in 1940, according to Bruccoli in Some Sort of Epic Grandeur).

About the time Gatsby was published, Scott met Ernest Hemingway for the first time—at the Dingo bar in Paris. Shortly thereafter, the two of them took a trip to Lyons to pick up the Fitzgeralds’ car, which was being repaired there. The only account we have of their meeting and of this trip is that offered by Hemingway in his posthumously published, and probably not very reliable, memoir, A Moveable Feast (1964). According to Hemingway, Scott, who “had very fair wavy hair, a high forehead, excited and friendly eyes and a delicate long-lipped Irish mouth that, on a girl, would have been the mouth of a beauty. . . .” (149), abruptly asked him “ ‘did you and your wife sleep together before you were married?’ ” (151). Then Scott got very drunk on champagne and passed out. Later in A Moveable Feast, Hemingway paints unflattering portraits of Zelda as “jealous of Scott’s work” (180) and as deliberately “making him jealous with other women” (181), and of Scott as perpetually drunk and insecure about his ability to please women sexually (he quotes Scott as claiming that “Zelda said that the way I was built I could never make any woman happy” [190]). Hemingway’s account notwithstanding, Scott, throughout the remainder of his life, maintained an at-times-supportive, albeit always uneasy and complicated, relationship with Hemingway.

For his part, Hemingway introduced Scott to many of the leading members of the American expatriate community in Paris, most notably Gertrude Stein and Sylvia Beach, the proprietor of Shakespeare and Company, the city’s leading literary bookstore and a gathering place for the local literati. But Scott and Zelda seemed to prefer the bars and nightclubs of the city to its literary salons. The tales of their antics replicated in many ways their similar behavior in New York in 1920. In his Ledger, Scott described that spring of 1925 in Paris as “1000 parties and no work” (Ledger 179).

Christmas 1925, Paris. Courtesy of Princeton University Library

After spending the summer of 1925 on the Riviera with the Murphys and their circle, the Fitzgeralds returned to Paris, where Scott began to plan his next novel and Zelda started ballet classes with Lubov Egorova. Scott also spent considerable time with Hemingway during the fall. He convinced Scribners to become Hemingway’s publisher when the latter’s publisher, Boni & Liveright, refused to publish The Torrents of Spring, Hemingway’s parody of Sherwood Anderson, who was a Boni & Liveright author. All the Sad Young Men, Scott’s third short story collection, appeared in February 1926 to generally admiring reviews and good sales; shortly thereafter, Scott and Zelda returned to the Riviera for the spring and summer. In June, Scott read the manuscript of Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises and suggested significant revisions—including cutting the first two chapters—which Hemingway made.

During that summer of 1926, the Fitzgeralds’ drinking and antisocial behavior became increasingly extreme and began to alienate the Murphys and others of their friends. One night, when Scott and Zelda met Isadora Duncan and the famed dancer openly flirted with Scott, Zelda threw herself down a flight of stone stairs in a fit of jealous rage. At one party given by the Murphys, a drunken Scott blithely tossed ashtrays around the room; at another, he smashed the hosts’ stemware. As the year came to a close, Scott had failed to make significant progress on his novel, the couple were again financially in dire straits, and their drinking was threatening their health and distancing them from their friends. “I wish I were twenty-two again with only my dramatic and feverishly enjoyed miseries,” he had plaintively written Perkins late in 1925, adding, “You remember I used to say I wanted to die at thirty—well, I’m now twenty-nine and the prospect is still welcome” (Life in Letters 131).

In December 1926, Scott and Zelda returned to the United States. After spending Christmas in Montgomery, they went to Hollywood, where Scott spent the first two months of 1927 working on “Lipstick,” a screenplay about a flapper, for starlet Constance Talmadge. In Hollywood, they partied and Scott became infatuated with seventeen-year-old actress Lois Moran, who apparently did not return his interest. Zelda’s response was to burn her clothes in a hotel bathtub and to throw a platinum watch Scott had given her early in 1920 before their marriage from the train window on the trip back east.

Upon their return, the Fitzgeralds rented Ellerslie, a nineteenth-century Greek Revival mansion at Edgemoor, located on the Delaware River, outside Wilmington. Still stung by Scott’s attentions to Lois Moran, Zelda resumed ballet studies—now with the Philadelphia Opera ballet—and also returned to writing humorous magazine articles. She sold three

of the latter before the end of 1927; significantly, the third was published under Scott’s byline, and many of her subsequent essays and stories bore the attribution “by F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald” because the magazines wanted to capitalize on his name and reputation. Initially, this did not appear to bother Zelda; increasingly, however, she became resentful and competitive toward her husband. This put a further strain on their marriage, a tension that was only made worse by Scott’s continuing failure to make significant headway on the novel he had been writing for two years.

During the early months of 1928, the intensity of Zelda’s ballet studies increased. In April, when the couple went to Europe for the summer, they settled in Paris so that she could study with the Russian ballet. But in Save Me the Waltz, Zelda wrote of that trip, “They hadn’t much faith in travel nor a great belief in a change of scene as a panacea for spiritual ills . . .” (Collected Writings 94–95). In late June, Scott met James Joyce at a dinner given by Sylvia Beach. That summer also saw Scott, who was feeling isolated and abandoned by his wife, thrown in jail twice in Paris for drunken behavior. When they returned to Ellerslie in October, he had made little progress on his novel. Back in Delaware during the fall and winter of 1928–1929, Zelda’s obsessive ballet studies continued. Although Milford quotes Gerald Murphy as remarking, “There are limits to what a woman of Zelda’s age can do and it was obvious that she had taken up the dance too late” (141), Zelda explains in Save Me the Waltz that she took up dancing so that “she would drive the devils that had driven her—that, in proving herself, she would achieve that peace which she imagined went only in surety of one’s self—that she would be able, through the medium of the dance, to command her emotions, to summon love or pity or happiness at will, having provided a channel through which they might flow” (Collected Writings 118).

Scott’s frustrations with his novel continued, and, as he later wrote in “Echoes of the Jazz Age” (1931), he was beginning to see around him signs that his and America’s boom years were coming to an end:

By this time contemporaries of mine had begun to disappear into the dark maw of violence. A classmate killed his wife and himself on Long Island, another tumbled “accidently” from a skyscraper in Philadelphia, another purposely from a skyscraper in New York. One was killed in a speak-easy in Chicago; another was beaten to death in a speak-easy in New York and crawled home to the Princeton Club to die . . . These are not catastrophes that I went out of my way to look for— these were my friends; moreover, these things happened not during the depression but during the boom. (Crack-Up 20)

When their two-year lease on Ellerslie expired in the spring of 1929, they returned to Paris so that Zelda could resume her ballet study with Egorova. She was also continuing her writing, but now it was fiction, a series of short stories that dealt with the lives of six young women. Five of these stories were published—all under a joint byline—and this put Zelda into direct competition with her husband, who was still struggling with his novel. The strain of writing and dancing was beginning to take a toll on Zelda’s twenty-eight-year-old body, and on her mental health, as well. And Scott continued to feel abandoned, as he explained in a plaintive note to Hemingway:

My latest tendency is to collapse about 11:00 and, with the tears flowing from my eyes or the gin rising to their level and leaking over, + tell interested friends or acquaintances that I havn’t a friend in the world and likewise care for nobody, generally including Zelda, and often implying current company—after which the current company tend to become less current and I wake up in strange rooms in strange palaces. The rest of the time I stay alone working or trying to work or brooding or reading detective stories—and realizing that anyone in my state of mind who has in addition never been able to hold his tongue, is pretty poor company. But when drunk I make them all pay and pay and pay. (Life in Letters 169)

When the Fitzgeralds returned to the Riviera for the summer and early fall, Scott managed to complete two chapters of his novel (Tender Is the Night would go through seventeen drafts and would not be published until 1934), and Zelda danced professionally for the first time in Nice and Cannes. But on the motor trip back to Paris in October, Zelda suddenly grabbed the steering wheel and tried to drive off a cliff; she continued to behave erratically throughout the fall and early winter of 1929–1930. As she said, “We went [to] sophisticated places with charming people but I was grubby and didn’t care” (Milford, Zelda 156). In September, she was offered a solo role in Aida by the San Carlo Opera Ballet Company in Naples, but, inexplicably, she turned it down. A February 1930 trip to North Africa, Scott’s attempt to give Zelda a rest from her frantic ballet studies, was not a success. In “My Lost City,” Scott misdated their receiving the news of the stock market crash as having occurred while they were on this trip (“we heard a dull distant crash which echoed to the farthest wastes of the desert” [Crack-Up 32]); but with the fall of the stock market, as he correctly noted in “Echoes of the Jazz Age,” “the most expensive orgy in history was over” (Crack-Up 21). Scott and Zelda’s personal crash was imminent, as well. When they returned to Paris, Zelda resumed her classes with Egorova, becoming pathologically dependent on her teacher and mentally and physically exhausted. When she entered Malmaison clinic outside Paris in April, the clinic’s report stated that upon admission, she was “continually repeating” this litany: “ ‘This is dreadful, this is horrible, what is going to become of me, I have to work, and I will no longer be able to, I must die, and yet I have to work. I will never be cured, let me leave” (Some Sort of Epic Grandeur 293). Her words were poignantly prophetic: Thereafter, she would never truly be cured, and although she would periodically leave the various clinics and institutions to which she had been committed, she never again really did resume a normal existence. Almost exactly ten years had elapsed between the date of the Fitzgeralds’ marriage, April 3, 1920, and the day, April 23, 1930, on which Zelda entered Malmaison.

After less than a month at Malmaison, Zelda discharged herself and returned home to Paris, where she resumed ballet lessons. After experiencing hallucinations and attempting suicide, however, she entered Val-Mont clinic in Glion, Switzerland, where she was examined in early June 1930 by Dr. Oscar Forel, who then had her transferred to his own clinic, Les Rives de Prangins at Nyon, on Lake Geneva. Shortly after Zelda entered Prangins, the Fitzgeralds wrote the two long letters of reminiscence mentioned earlier.

50. TO ZELDA

[Summer 1930]

AL (draft), 7 pp.1

[Paris or Lausanne]

Written with Zelda gone to the Clinque

I know this then—that those day when we came up from the south, from Capri, were among my happiest—but you were sick and the happiness was not in the home.

I had been unhappy for a long time then—when my play failed a year and a half before, when I worked so hard for a year[,] twelve stories and novel and four articles in that time with no one believing in me and no one to see except you + before the end your heart betraying me and then I was really alone with no one I liked. In Rome we were dismal and was still working proof and three more stories and in Capri you were sick and there seemed to be nothing left of happiness in the world anywhere I looked.

Then we came to Paris and suddenly I reallized that it hadn’t all been in vain. I was a success—the biggest one in my profession— everybody admired me and I was proud I’d done such a good thing. I met Gerald and Sara who took us for friends now and Ernest who was an equeal and my kind of an idealist. I got drunk with him on the Left Bank in careless cafés and drank with Sara and Gerald in their garden in St Cloud but you were endlessly sick and at home everything was unhappy. We went to Antibes and I was happy but you were sick still and all that fall and that winter and spring at the cure and I was alone all the time and I had to get drunk before I could leave you so sick and not care and I was only happy a little while before I got too drunk. Afterwards there were all the usuall penalties for being drunk.

Finally yo

u got well in Juan-les-Pins and a lot of money came in and I made [one] of those mistakes literary men make—I thought I was a man of the world—that everybody liked me and admired me for myself but I only liked a few people like Ernest and Charlie McArthur2 and Gerald and Sara who were my peers. Time goes bye fast in those moods and nothing is ever done. I thought then that things came easily—I forgot how I’d dragged the great Gatsby out of the pit of my stomach in a time of misery. I woke up in Hollywood no longer my egotistic, certain self but a mixture of Ernest in fine clothes and Gerald with a career—and Charlie McArthur with a past. Anybody that could make me believe that, like Lois Moran did, was precious to me.

Ellerslie, the polo people, Mrs. Chanler3 the party for Cecelia4 were all attempts to make up from without for being undernourished now from within. Anything to be liked, to be reassured not that I was a man of a little genius but that I was a great man of the world. At the same time I knew it was nonsense—the part of me that knew it was nonsense brought us to the Rue Vaugirard.

But now you had gone into yourself just as I had four years before in St. Raphael—and there were all the consequences of bad appartments through your lack of patience (“Well, if you want a better appartment why don’t you make some money”) bad servants, through your indifference (“Well, if you don’t like her why don’t you send Scotty away to school”) Your dislike for Vidor,5 your indifference to Joyce I understood—share your incessant entheusiasm and absorbtion in the ballet I could not. Somewhere in there I had a sense of being exploited, not by you but by something I resented terribly no happiness. Certainly less than there had ever been at home—you were a phantom washing clothes, talking French bromides with Lucien or Del Plangue6—I remember desolate trips to Versaille to Rhiems, to LaBaule undertaken in sheer weariness of home. I remember wondering why I kept working to pay the bills of this desolate menage. I had evolved. In despair I went from the extreme of isolation, which is to say isolation with Mlle Delplangue, or the Ritz Bar where I got back my self esteem for half an hour, often with someone I had hardly ever seen before. In the evenings sometimes you and I rode to the Bois in a cab—after awhile I preferred to go to Cafe de Lilas and sit there alone remembering what a happy time I had had there with Ernest, Hadley,7 Dorothy Parker + Benchley two years before. During all this time, remember I didn’t blame anyone but myself. I complained when the house got unbearable but after all I was not John Peale Bishop—I was paying for it with work, that I passionately hated and found more and more diffi-cult to do. The novel was like a dream, daily farther and farther away.

This Side of Paradise

This Side of Paradise The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby Tender Is the Night

Tender Is the Night Tales of the Jazz Age (Classic Reprint)

Tales of the Jazz Age (Classic Reprint) The Beautiful and Damned

The Beautiful and Damned The Pat Hobby Stories

The Pat Hobby Stories The Love of the Last Tycoon

The Love of the Last Tycoon The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Six Other Stories

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Six Other Stories O Grande Gatsby (Penguin)

O Grande Gatsby (Penguin) Babylon Revisited and Other Stories

Babylon Revisited and Other Stories The Crack-Up

The Crack-Up Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda The Fantasy and Mystery Stories of F Scott Fitzgerald

The Fantasy and Mystery Stories of F Scott Fitzgerald Flappers and Philosophers

Flappers and Philosophers The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories (Penguin Classics)

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories (Penguin Classics) I'd Die For You

I'd Die For You All the Sad Young Men

All the Sad Young Men The Last Tycoon

The Last Tycoon The Best Early Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Best Early Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald This Side of Paradise (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

This Side of Paradise (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) A Life in Letters

A Life in Letters Beautiful and Damned (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Beautiful and Damned (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories Tales of the Jazz Age

Tales of the Jazz Age Babylon Revisited

Babylon Revisited Complete Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald UK (Illustrated)

Complete Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald UK (Illustrated)